In the case of the semi-trailer, such uses could be delivering goods to customers or transporting goods between warehouses and the manufacturing facility or retail outlets. All of these uses contribute to the revenue those goods generate when they are sold, so it makes sense that the trailer’s value is charged a bit at a time against that revenue. Suppose that trailer technology has changed significantly over the past three years and the company wants to upgrade its trailer to the improved version while selling its old one. The two main assumptions built into the depreciation amount are the expected useful life and the salvage value.

- The beauty of this formula is that it’s one-size fits all—just fill the depreciation table with this formula, and everything will calculate.

- With a book value of $73,000 at this point (one does not go back and “correct” the depreciation applied so far when changing assumptions), there is $63,000 left to depreciate.

- And what will most likely actually happen is that Apple will continue to borrow and offset future maturities with additional borrowings.

- Once you discover there is a TRANSPOSE function, you think life is simple and your problems (well, you modelling problems anyway!) are over.

- OR If [Depreciation Year] is less than [Capex Year],Take $0.Here, we’re saying that if the Depreciation Year is more than 6 years after the Capex Year, or if the Depreciation Year is before the Capex Year, no depreciation should be taken.

Useful Life and Accelerated Depreciation

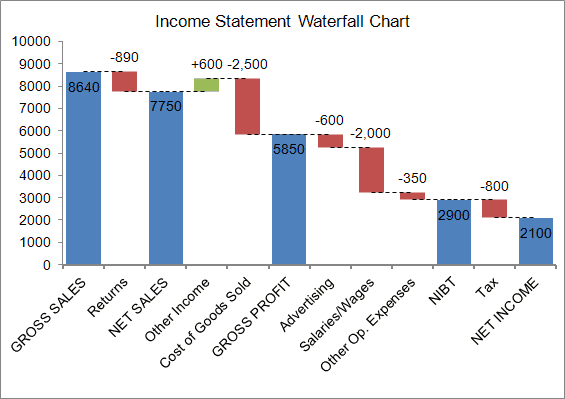

The difference between the end-of-year PP&E and the end-of-year accumulated depreciation is $2.4 million, which is the total book value of those assets. Below is a sample straight-line depreciation schedule, or “Waterfall”, for a single asset class, with a single useful life. The principles we’re about to describe can easily be extended to a depreciation waterfall that has detail by month. Here’s a standard, boring way to calculate depreciation expense from a list of capital expenditures and the depreciation schedule. To keep this simple, let’s not make this an accelerated depreciation-type problem.

Deferred tax assets and liabilities

We can also convert this total to a monthly depreciation amount by dividing by the [Months in Depreciation Year]. While this can be a time consuming process, the good news is that if you follow the above steps correctly, you will locate the error and your model will balance. One exception to this is when modeling private companies that amortize goodwill. This is an ideal approach for copying and transposing data from one source to another where links are not required. Aside from the inherited formatting, the main disadvantage here though is that depending upon the nature of the source data and how it is copied, updates in the original data will not flow through to the destination range. Depreciation is how an asset’s book value is “used up” as it helps to generate revenue.

Common stock and APIC

As can be plainly seen from the illustration (above), the formatting as well as the content will be transposed. For the purposes of simplification, I am going to assume that we are looking to transpose data from going across a row to going down a column (the concepts are similar if columns are transposed into rows). Get instant access to video lessons taught by experienced investment bankers.

The differences between ‘Straight line service life’ and ‘Straight line life remaining’ in D365FO (or AX)

In a 3-statement model, the net income will be referenced from the income statement. Meanwhile, barring a specific thesis on dividends, dividends will be forecast as a percentage of net income based on historical trends (keep the historical dividend payout ratio constant). Using this new, longer time frame, depreciation will now be $5,250 per year, instead of the original $9,000. That boosts the income statement by $3,750 per year, all else being the same. It also keeps the asset portion of the balance sheet from declining as rapidly, because the book value remains higher.

Other non-current assets and liabilities

There are always assumptions built into many of the items on these statements that, if changed, can have greater or lesser effects on the company’s bottom line and/or apparent health. Assumptions in depreciation can impact the value of long-term depreciation waterfall assets and this can affect short-term earnings results. In other words, in this Depreciation Year, take all of the depreciation that hasn’t been taken yet so that we’ll have now depreciated the Capex Year’s purchases entirely.

There are a variety of factors that can affect useful life estimates, including usage patterns, the age of the asset at the time of purchase and technological advances. Similar things occur if the salvage value assumption is changed, instead. Suppose that the company changes salvage value from $10,000 to $17,000 after three years, but keeps the original 10-year lifetime. With a book value of $73,000, there is now only $56,000 left to depreciate over seven years, or $8,000 per year. That boosts income by $1,000 while making the balance sheet stronger by the same amount each year.

Once repeated for all five years, the “Total Depreciation” line item sums up the depreciation amount for the current year and all previous periods to date. The average remaining useful life for existing PP&E and useful life assumptions by management (or a rough approximation) are necessary variables for projecting new Capex. Therefore, companies using straight-line depreciation will show higher net income and EPS in the initial years.

Instead, the cost is placed as an asset onto the balance sheet and that value is steadily reduced over the useful life of the asset. This happens because of the matching principle from GAAP, which says expenses are recorded in the same accounting period as the revenue that is earned as a result of those expenses. While a company’s financial reports—the income statement, the balance sheet, the cash flow statement, and the statement of owners’ equity—represent the company’s financial health and progress, they can’t provide a perfectly accurate picture. The formula to calculate the annual depreciation is the remaining book value of the fixed asset recorded on the balance sheet divided by the useful life assumption.